New Zealand troops began returning from overseas in small numbers in late 1914. The first arrivals, from Samoa, were followed by many more from Egypt and Turkey, and later from England and France. Most were sick or wounded, but some were sent back because of misconduct. More troops returned home from early 1918, in line with the NZEF’s scheme for demobilisation. Most were ‘low category men’ such as those deemed permanently unfit, who were sent home to free up hospital beds for the heavy casualties that were anticipated. Some fit men who had served for several years were sent home on furlough (leave of absence).

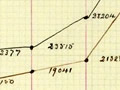

By the time of the armistice with Germany in November 1918, nearly 30,000 men had returned home or were on their way. But more than 50,000 remained overseas. The Defence Department arranged the return of the vast majority of these troops during 1919. It also transported thousands more people: the wives and children of soldiers, civilian war workers, and New Zealanders who had served in the British army or navy.

New Zealanders welcomed the returning troops in a variety of ways. Public enthusiasm for particular arrivals varied, and government policies first encouraged, then discouraged, public receptions.

Some troops, such as the first large group of Gallipoli wounded who returned in 1915, and the first large group of Main Body men who returned in 1919, received boisterous public welcomes which began at the first port of call and continued to the other end of the country. Others journeyed to their home towns with little fanfare and were welcomed mainly by the local community, friends and families.

Early arrivals

The first men to return to New Zealand from war were members of the Samoan Advance Party. Twenty-one men deemed medically unfit arrived in Wellington on the troopship Moeraki in early September 1914. Another 70 mostly fit men arrived in Auckland on the troopship Monowai a few days later. Newspapers reported these events widely, as the men brought back first-hand accounts of the voyage to and capture of German Samoa. They received little by way of formal welcome. Public attention was focused on the anticipated departure of the Main Body to the northern hemisphere, and these men had been away for less than one month. More men returned to Auckland from Samoa in November 1914, again with little fanfare.

Service after Samoa

For a number of this first group of men, the return voyage to Apia was the beginning and end of their war. Others went on to serve at Gallipoli, in the Middle East or on the Western Front. Thomas Fordyce of Auckland, for example, went to Egypt in mid-1915 but was invalided home in mid-1916. Francis Hatwell of Hawke’s Bay was killed in action on the Somme in France on 24 April 1918.

Most of the men who returned from Samoa on the Moeraki were suffering from mild complaints; ‘bad teeth, sore feet, etc’. [1] Albert Hanlon of Wellington had a bunion. But some had serious ailments. Laurie Collins of Auckland was found to have epilepsy, a condition that had been overlooked during the hasty medical examinations undertaken before the Advance Party’s departure in August 1914.

The situation was similar for the first Egypt-bound men who returned to New Zealand from early 1915. They arrived in small numbers on various troopships at diverse ports to no apparent welcome. Some of the men were sent home because they were medically unfit. Others were being punished for misconduct, such as missing the outward troopship at Albany, or for refusing to be inoculated against typhoid. Newspapers showed interest in first-hand accounts of the voyage to Alexandria, and the reasons the men gave for their ill-health or misconduct.

The Samoan Advance Party returns

The first hearty welcomes were tendered to the large groups of men and nurses of the Samoan Advance Party who returned to New Zealand in March and April 1915. Arriving on the troopship Talune in Wellington just under a month apart, both groups were greeted by the prime minister, the minister of defence, the mayor, army officers, relatives and friends, and members of the public.

Why was their return celebrated in a way that of their predecessors was not? As the bulk of the Samoan Advance Party, they embodied the seizure and occupation of German Samoa. Most were fit men who were being relieved so that they could go ‘to the front’ and contribute further to the war effort. In fact many of these men did sign up for the reinforcements. [2] So did all the nurses who had gone to Samoa with the Advance Party.

The wounded return from Gallipoli

Wellington’s welcomes to the large groups of mainly fit men returning from Samoa paled in comparison to those the country gave the first large groups of wounded which returned from Gallipoli from mid-1915. They were given receptions at their first port of call and in all the main centres, and feted at railway stations as they travelled home.

A few men returned to New Zealand from Gallipoli as early as June 1915. Newspapers took an interest in their first-hand accounts, but they didn’t receive a special welcome. Seddon Gabriel of Petone, who arrived on the Wimmera on 4 June 1915 because of illness, was said to be the first man who had set foot on Gallipoli to return. His account of the landing was published widely – although his personnel file suggests he may have been deemed medically unfit prior to this action. A ‘confused recollection of that historic landing’ by Frederick Phelan of Auckland, who returned on the Moeraki a few days later (and was also on the ‘sick-list’ by 25 April) generated similar interest. [3]

The first large group of Gallipoli wounded arrived to great fanfare in Wellington on 15 July 1915 as part of a draft of around 300 men on the Willochra. Approximately 2000 people - next of kin, officials and journalists – waited for the men in a reserved area beside the berth. The general public assembled on adjacent wharves and along the route the men took from the ship to their official reception at the Town Hall.

Men bound for Auckland and other North Island areas served by the Main Trunk Line were dispatched on a specially outfitted ‘Red Cross train’ that evening. [4] They received further welcomes along the way and at Auckland’s railway station. Here, as in Wellington, they were conveyed by motor car to an official reception at the Town Hall.

Many of the South Island men reboarded the Willochra, which left Wellington on 16 July. They received similar welcomes and receptions on their arrival at Lyttelton and Port Chalmers, and in Christchurch and Dunedin. Rail or steamer passes were provided for men returning to regions such as the West Coast.

A similar approach was taken to welcoming home other large groups of Gallipoli wounded over the following months. Drafts of 400-500 men arrived on the Tahiti in September and on the Tofua and the Willochra in October.

None of these arrangements went perfectly, particularly for loved ones waiting anxiously down the line. Ships and trains were delayed for various reasons, disrupting planned receptions. For example, Christchurch’s plans to welcome the men from the Willochra – including with a procession through the city’s streets - were upset when the train from Lyttelton arrived later than anticipated. Men who were delayed or bound for rural areas often made their own way home. Sometimes they missed family and friends who had travelled to meet them. More often, they merely frustrated the efforts of outlying communities to give them a fitting welcome.

From the return of the Willochra onwards, the Defence Department endeavoured to notify local mayors of the return of men to their areas. This was not always possible, and each return had an inevitable sequel when a mayor complained to the prime minister that the department had failed to give him adequate notice. Procedures were steadily improved. As well as marking all telegrams to mayors on these matters as ‘urgent’, the department began to detail ‘a competent officer’ to travel with each group of returning men and take responsibility for notifying mayors of their expected time of arrival. [5]

Hospital ships return

More medically unfit men were sent back to New Zealand during 1916. Some arrived individually or in small groups to relatively little fanfare. Large groups generally received an official welcome and a reception at their first port of call, and these events were replicated in places to which a significant number of them travelled on. Public and official interest was greater when there was something noteworthy about an arrival, such as when the Ruahine docked in Auckland in January 1916 with the first men to return from Gallipoli after convalescing in England.

Particularly enthusiastic welcomes were extended to the large groups of men who came home on the country’s two hospital ships. More than 300 arrived on the Maheno in January, April and December 1916, and more than 150 on the Marama in October. Events to welcome back the country’s wounded heroes also gave the public and officials opportunities to celebrate the country’s outfitting of the hospital ships and the courageous work of their medical staff.

It’s unclear how much the returned men appreciated these functions, as newspaper reporters paid little attention to their reactions. There are hints that their response was at best subdued. The men who returned on the Willochra in July 1915 were described only as seeming ‘to enjoy their home-coming very much’ and as responding ‘in a way that suggested their gratification at being among friends’. [6] Other accounts suggest that many found the attention difficult or bothersome.

Whatever the men thought of the receptions, the Defence Department encouraged them to attend. From late 1915 attendance was compulsory; this was spelt out in the Returned soldiers’ handbook. The instruction remained in force despite objections from those who worked with and knew the feelings of the returned men.

Fortunately for men who returned later in the war, communities soon began to scale back their arrangements.

‘Regular’ returns

By 1917 most of the main centres had curtailed their arrangements for welcoming returning men. Those closely involved in organising receptions had probably known for some time that the men weren’t overly keen on them. Elaborate plans also continued to be upset by the lack of certainty about when the men would arrive. While drafts continued to return sporadically, efforts were made to work around this difficulty. But as groups of men began to arrive more frequently, most centres scaled back their activities.

Auckland seems to have made the first concession. In March 1916, a small group of men who had landed at Wellington before travelling north by steamer were received in a large shed at the wharf, rather than at the Town Hall. This approach was so successful that it became the norm in Auckland.

From late 1916 the other main centres began to take a similar approach. Extended welcomes at the wharves or railway station replaced receptions and luncheons at the town hall or another public building.

These welcomes were not entirely different from those they superseded. Next of kin and officials were given pride of place, crowds gathered (in proportion to the size of the group returning), and the men were presented with gifts of fruit, flowers and cigarettes before being driven away by the local volunteer motor corps.

These men were pleased not to be paraded around in public. One of them told the Dominion in June 1917 that he ‘did not want to be made a little tin god of’. [7] They also benefited from a gradual reduction in the number and length of speeches. Men travelling on from the first port of call also had fewer receptions to endure on their way home. In late 1917 the mayors of Auckland and Wellington agreed that they would only put on an official reception when their city was the first port of call. Those whose destination was outside the main centres were sometimes still welcomed back to their home towns.

The introduction of low-key receptions in the main centres led some to argue that not enough was now being done to welcome the men home. But this practice remained the norm until the end of the war, after which large numbers of men returned and the government revisited the issue.

Demobilisation

More troops returned home from early 1918, in line with the NZEF’s scheme for demobilisation. Most were ‘low category men’ such as those deemed permanently unfit, who were sent home to free up hospital beds for the heavy casualties that were anticipated. [8] Some fit men who had served for several years were sent home on furlough (leave of absence). As a result, by the time of the armistice with Germany in November 1918 nearly 30,000 men had returned home or were on their way. But more than 50,000 remained overseas.

In the first few weeks after the armistice the Defence Department continued to return mainly sick, wounded and low-category men who were fit to travel. They also sent back ‘urgently required pivotal men’ and, if space allowed, the wives and families of returning men. [9] The NZEF could not immediately demobilise fully – the signing of an armistice did not necessarily mean peace. In early December Defence Minister Allen told Parliament that he hoped to return ‘the whole of the sick and wounded’ to New Zealand before the end of March 1919. But he could not say when the fit men would arrive – it might not be until ‘peace had been decided, or perhaps signed’. [10]

In the event, the troops and the public did not have to wait that long. By mid-December the department had secured the release of 1914/1915 Main Body men who were still serving in France, and of the (Māori) Pioneer Battalion. Allen argued that the return of New Zealand troops should be expedited, ‘as they have so far to go’. [11] More good news came in late January. The New Zealand Division, which was on occupation duty in Germany, would not be required to remain there until peace was declared.

The government had already decided that men should return home in the order that they had gone overseas – with some exceptions. Married men were given priority within their class, so those who had left New Zealand in 1914 returned before single men who had departed in that year. Men ‘specially required in the Dominion’ could be ‘returned from time to time as requested’. [12] There was ‘urgent priority of return’ for coal miners, apprentices, public works employees, and medical and dental students. The government also called for priority to be given to railwaymen and schoolteachers – within their class, and if shipping was available. [13]

Initial predictions of rapid demobilisation proved to be over-optimistic. The Christmas and New Year holidays and then a strike by shipwrights slowed progress. These delays led to several riots by troops, including New Zealanders at Sling Camp in Wiltshire, England in March 1919. There was also a perception that individuals or groups of men were being fast-tracked unfairly. Despite the delays, the vast majority of New Zealand troops made it home during 1919. Most came in drafts numbering in the hundreds, and in some cases more than 1000. Some men returned independently, individually or in small groups.

Education on board

Some commanding officers made attendance compulsory at the education classes organised during the voyage home. Reasons given for not doing so included lack of interest from the men, and shortages of suitable facilities and instructors. Reporting on the voyage of the Kia Ora between March and May 1919, its commanding officer noted that he decided to make classes voluntary because the majority of the men on board ‘were implicated in the roits [sic] in Sling Camp’, where parades and education classes had been made voluntary. [14]

At its first port of call, usually Wellington or Auckland, each draft was welcomed by the mayor and next of kin or their proxies. The Defence Department did not want large numbers of family members and friends to meet men when they arrived in the country. In April 1918 it stopped giving them free travel to ports, and they were excluded from the special trains put on for the men. The official reason was that Admiralty instructions made it impossible to publicise reliable arrival dates. But the department also feared that transporting large numbers of next of kin to and from the ports would both disrupt the travelling public and slow the despatch of soldiers to their homes, especially once demobilisation began en masse. When Admiralty restrictions eased in January 1919 the department began to give next of kin earlier and clearer information about arrival dates. But it continued to discourage them from travelling to their loved one’s first port of call.

Despite these restrictions, crowds sometimes gathered on the waterfront, especially for large arrivals. When the Oxfordshire berthed in Auckland in February 1919 - on a Saturday, fully bedecked and carrying more than 1000 troops - people ‘crowded to the waterfront in thousands’. [15] The arrival of large groups of brides and babies also generated considerable interest.

Most drafts were serenaded by a patriotic band and given fruit and cigarettes. Sometimes patriotic organisations put on tea and other light refreshments. The men generally couldn’t get an alcoholic drink anywhere near the port. War regulations allowed the minister of defence to restrict the sale and supply of liquor when troopships arrived. In practice Allen usually closed hotel bars to drafts of more than 50 men.

After these few signs of welcome the men were driven off in cars provided by the local volunteer motor corps, or caught special or ordinary trains or ships. Those who stayed on the troopship until its next port of call, or travelled on by train or ship, often received similar welcomes at their next destination. Local dignitaries, next of kin, bands and the volunteer motor corps greeted men arriving in Wellington after earlier landfalls in Auckland, Christchurch or Dunedin. Smaller cities and towns continued to welcome men as they had earlier in the war. Interviewed for an oral history project in the 1980s, Stan (Sydney George) Stanfield, recalled his treatment after his return on the Oxfordshire in February 1919:

For the first few weeks … you’d be welcomed home by people that you’d never met before. They’d stop you on the streets and pat you on the back and welcome you home, glad to see you back and all this sort of thing. [16]

Whilst brief welcome ceremonies sped up the men’s return home, quarantine or red tape often delayed them. Quarantine measures were imposed when there had been illness on board, and the Public Health Department implemented more general restrictions when disease was prevalent at an overseas port. For example, an influenza outbreak in Australia in early 1919 led to the minister for public health enforcing a 24-hour quarantine on all ships arriving from overseas.

The troops generally accepted the need for quarantine but often grew frustrated with delays caused by bureaucracy. For example, those in charge of the troops on the Briton delayed their disembarkation at Lyttelton until missing equipment worth £200 had been replaced. These men had already been quarantined for 24 hours and – fed up with waiting – they rushed the tender that was to take them ashore. In the resulting confusion, North and South Islanders got mixed up and many men missed connecting trains or ships.

Exceptions

As more drafts returned to New Zealand, some people asked if they should be welcomed with greater ceremony. But the Defence Department continued to give the highest priority to getting them home. Defending this position, Allen noted that receptions could not be held at every port, as ‘the men themselves get tired of them’; the most natural venue was wherever the men lived. [17]

Notable among exceptions to this approach was the welcome for the first large group of fit Main Body men, who arrived on the Hororata in March 1919. As the ship sailed into Wellington Harbour, the city’s forts fired salvos to which the Hororata responded with rockets.

As the Hororata waited offshore, it was circled by boats carrying next of kin and the men received a message from Sir James Allen: they would be welcomed the next day, but not ‘detained for speeches’. [18] When the ship finally berthed, dignitaries including Allen, other ministers and city councillors joined the mayor and next of kin on the wharf. A band accompanied several hundred members of the Public Service Ladies’ Choir, and more bands played at key points between King’s Wharf and Post Office Square.

Crowds gathered along this route to see the men. Those who were not anxious to get home enjoyed refreshments at the Wellington Returned Soldiers’ Lambton Quay club and an informal social at the Town Hall that evening. Men who journeyed on by train or ship received excited welcomes in their home towns. Bunting flew, crowds gathered and bands played.

The Pioneer Battalion received a much more extensive welcome than was given to any other troops, probably because such ceremonies were central to Māori protocol and could not easily be set aside. The Pioneer Battalion was also one of only two NZEF formations – and the only battalion – to return home as a unit. The opportunity for a proper welcome and the special significance of the arrival of a complete unit saw both Pākehā and Māori communities make a huge effort to greet it. The welcome began when the Westmoreland arrived in Waitematā Harbour on the evening of 5 April, carrying more than 1000 battalion members (around 400 remained in France and England, mainly in hospital).

Early the following morning a plane from Kohimarama Flying School dropped cigarettes, sweets, buttonholes and messages of welcome for the men. As the ship made its way to the wharf, harbour defence guns fired a salute, steamers sounded their sirens and bands played patriotic airs. Dignitaries, including Sir James Allen, greeted the men and gave brief speeches of welcome before they marched past thousands of cheering Aucklanders to the Domain for a pōwhiri. Here they were addressed again by Allen and by representatives of iwi from throughout the country. After a break for ‘a feast of welcome’, the ceremonies continued. [19] Events in the afternoon were more sombre, with a tangi for the departed, the singing of karakia and a service conducted by the Anglican Bishop of Auckland. Battalion members were greeted with more pōwhiri and civic receptions as they neared home.

Others were welcomed as they arrived back in their home towns, and at receptions held by clubs and workplaces over the following days and weeks. Allen hosted a reception for returned nurses in Wellington, as did the Trained Nurses’ Association in Auckland. New Zealand’s returning Victoria Cross recipients were all feted at civic receptions, some more than once.

The country’s conscientious objectors were also welcomed home by their supporters at events organised by trade unions. The most elaborate welcome was put on for former Grey district MP Paddy Webb after he was released from prison in September 1919. Webb was given receptions in Wellington, Christchurch and on the West Coast. In Greymouth, several thousand people crowded around the railway station to welcome him. Over the following days Webb attended a reception at the Opera House, a social and dance at the Druids’ Hall and another reception at Rūnanga.

Final returns

Most of the other men who returned in 1919 received a similar welcome to that for troops immediately after the armistice. The majority continued to arrive in drafts numbering from the hundreds to over 1000, while others arrived independently. Most still made landfall in Wellington or Auckland, but a few ships - mainly those carrying predominantly Otago or Canterbury men – berthed first at Port Chalmers or Lyttelton. May 1919 was a big month for Lyttelton (and Christchurch), as three troopships arrived within days of each other.

A mother's worry

Charles Morse remembered his first sight of his family from the Kia Ora in June 1919:

'They quarantined us for 24 hours. A mate came down and said, “There’s someone calling out to you from a boat.” I ran up on deck and I could see these people in a motorboat; they were hiring them out. There were three white-haired people. I knew old Uncle Jim and Aunty Sarah. Then there was this other white-haired woman. I yelled out to Uncle Jim to see who this other woman was. He said, “You fool. It’s your mother.” Her hair had turned from jet black to pure white in the four years, she worried so much. Every time she saw one of these telegraph people coming up the road that was another grey hair.' [20]

Arriving drafts continued to be welcomed by the local mayor, family, friends and a patriotic band, and with gifts of fruit and cigarettes. In Auckland a boat carrying next of kin often circled the ship before it berthed. The authorities still gave priority to despatching the men to their homes via the local volunteer motor corps, or by special or ordinary train or boat. Those heading for southern ports sometimes remained on their ship in Auckland. Smaller cities and towns continued to welcome their men, as they arrived home and at subsequent events.

By early 1920 the drafts of men returning had dwindled from the hundreds to the tens. They continued to be welcomed until their numbers fell to a handful. The last draft of a few men arrived on the Athenic in September 1920, apparently to little or no welcome. The very last men – some wounded and some from NZEF headquarters in London - returned to New Zealand in 1921.

Further information

This article was written by Imelda Bargas and produced by the NZHistory team.

Primary sources

Contemporary newspapers (many of which can be searched on the Papers Past website) and files held at Archives New Zealand provided much of the source material for this feature. These Archives New Zealand record groups were especially useful:

- Army Department [AAYS] Inwards letters and registered files [8638], former Archives reference AD1, including record numbers: 15 Ceremonies, entertainments, etc; 49 Medical; 56 Records; 74 Repatriation; 75 Demobilisation

- Army Department [AAYS] Base Records – Registered Files [8694], former Archives reference AD78

- War Archives [ACID] New Zealand Expeditionary Force Headquarters (NZEF HQ) [17590], former Archives reference WA231. Not all items in the ACID record group can be ordered via Archway – for more information, see these finding aids: http://www.archway.archives.govt.nz/ViewEntity.do?code=ACID]

Books

For a general overview of New Zealand's contribution to the First World War at home, see:

- Imelda Bargas and Tim Shoebridge, New Zealand’s First World War heritage, Exisle Publishing, Auckland, 2015

Other key sources included:

- A.D. Carbery, The New Zealand Medical Service in the Great War 1914-1918, Whitcombe & Tombs, Auckland, 1924

- Lieutenant H.T.B. Drew (ed.), The war effort in New Zealand, Whitcombe & Tombs, Auckland, 1923

- Christopher Pugsley, On the fringe of hell: New Zealanders and military discipline in the First World War, Hodder & Stoughon, Auckland, 1991

- Anna Rogers, While you’re away: New Zealand nurses at war 1899-1948, Auckland University Press, Auckland, 2003

- Colonel H. Stewart, The New Zealand Division 1916-1919: a popular history based on official records, Whitcombe & Tombs, Auckland, 1921

- John Studholme, Some records of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force: unofficial, but compiled from official records, Government Printer, Wellington, 1928

- War, 1914-1918. New Zealand Expeditionary Force: its provision and maintenance, Government Printer, Wellington, 1919

- War Regulations Acts, 1914-1918, Fifth Edition, Government Printer, Wellington, 1919

- Val Wood, War brides: they followed their hearts to New Zealand, Random Century, Auckland, 1991

See also these edited collections of oral history:

- Nicholas Boyack and Jane Tolerton, In the shadow of war: New Zealand soldiers talk about World War One and their lives, Penguin, Auckland, 1990

- Jane Tolerton, An awfully big adventure: New Zealand World War One veterans tell their stories, Penguin, Auckland, 2013

Notes

[1] Dominion, 8 September 1914, p. 7.

[2] Evening Post, 22 March 1915, p. 8.

[3] New Zealand Herald, 15 June 1915, p. 8; Marlborough Express, 18 June 1915, p. 2.

[4] Evening Post, 16 July 1915, p. 3.

[5] Ceremonies, entertainments, etc. – Reception sick and wounded returning, AAYS 8638 AD1753/15/58, Archives New Zealand.

[6] Evening Post, 15 July 1915, p. 8; Auckland Star, 16 July 1915, p. 3.

[7] Evening Post, 15 July 1915, p. 8; Auckland Star, 16 July 1915, p. 3.

[8] A. D. Carbery, New Zealand medical service in the Great War 1914-1918, pp. 483-5.

[9] ‘NZEF Circular Memorandum UK 214, Notes on demobilisation’, in Reports by Gen. Richardson in UK No. 23-32 Nov 1917-Feb 1919, ACID 17590 WA/231/11, ANZ.

[10] New Zealand parliamentary debates, vol. 183, 1918, pp. 955-6.

[11] Auckland Star, 14 January 1919, p. 4.

[12] Demobilisation – Demobilisation scheme – NZEF [New Zealand Expeditionary Force] – General File, 1919, AAYS 8638 AD1/1050/75/1/1, ANZ.

[13] Demobilisation – Priority of return – men for essential industries, AAYS 8638 AD1/1052/75/17/1, ANZ.

[14] Records – Returning drafts – Records and organisation on voyage, AAYS 8638 AD1/1015/56/252, ANZ.

[15] Auckland Star, 3 February 1919, p. 8.

[16] Nicholas Boyack and Jane Tolerton, In the shadow of war: New Zealand soldiers talk about World War One and their lives, Penguin, Auckland, 1990, p. 44.

[17] Dominion, 5 February 1919, p. 6.

[18] Evening Post, 14 March 1919, p. 8, 5 February 1919, p. 6.

[19] Auckland Star, 7 April 1919, p. 5.

[20] Jane Tolerton, An awfully big adventure: New Zealand World War One veterans tell their stories, Penguin, Auckland, 2013, pp. 270, 272.