Current Buildings

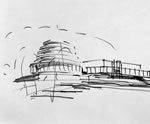

Beehive and Parliament House. View as panorama.

Parliament House

In 1907 fire destroyed all the buildings at Parliament, except for the library. Deciding what to do next was a difficult task, made worse by the fact that the House had to go about its business in the cramped old Government House, located across Sydney Street.

In February 1911 Prime Minister Joseph Ward anounced a competition for designs among New Zealand architects. Thirty-three entries were received, with the winning design (from Government Architect John Campbell) selected by Colonel Vernon, former Government Architect for New South Wales. Another of Campbell's entries won fourth place, and the two were blended for the final building design.

The idea was to have a new Parliament House in brick faced with stone in the Edwardian neo-Classical style then popular for grand public buildings. It would be built in two stages on a big flat plateau created between the library and old Government House. The first stage, including both chambers, would be built without interfering with old Government House. The second stage, including a huge new library, would extend the building south to replace it.

Cost got in the way from the start. When William Massey became Prime Minister in 1912 he reluctantly let the first stage go ahead, but said no to the roof domes and ornamentation. Construction began early in 1914 but fell behind schedule because suitable Takaka marble was hard to find, and the war created shortages of labour and materials.

By around 1917 the top floor had been added and the grounds had been levelled, but everything was late. MPs were so desperate to get out of the old Government House that Parliament moved into the incomplete buildings in 1918. Construction continued around them until work on the southern wall petered out in 1922, leaving it incomplete. Parliament House had to wait until 1995 for an official opening when Queen Elizabeth II did the honours.

It would never be finished. Modernists did not like Edwardian neo-classicism and others worried about earthquake risks. Some called for demolition. Doubts remained until the 1980s when the government, heeding the heritage call, decided to strengthen and refurbish the buildings.

Maori Affairs Committee rooms

Former Maori Affairs Committee Room showing portraits of Maori MPs and a large copy of the Treaty of Waitangi. View as panorama.

A special room for the select committee dealing with Maori Affairs opened in 1922. Carvings denoting the entrance to a whare runanga were fixed to a wall and on the architraves of the doors. The room was substantially renovated in 1955 under the supervision of John Grace, the private secretary to the Minister of Maori Affairs. A large panel reproducing the Treaty of Waitangi was mounted on a wall, which also displayed coloured portraits of the prominent Maori MPs James Carroll, Te Rangi Hiroa (Peter Buck), Maui Pomare and Apirana Ngata. Red and black kowhaiwhai decorated the ceiling and cornices, the replica whare runanga entrance was restored, and tukutuku panels were extended around the walls.

Maori Affairs Committee Room, Maui Tikitiki-a-Taranga. View as panorama.

After the 1990s refurbishment of Parliament House, a new Maori Affairs Committee room, Maui Tikitiki-a-Taranga, was located on the ground floor. The room takes its name from Maui who, in Maori history, fished the North Island of New Zealand from the sea.

Detail of panel.

The carvings (left to right in the image above) show Maui, his mother Taranga, and Hinetitama and Tanenuiarangi; they are set in tukutuku panels which represent Tane's journey to acquire the three baskets of knowledge (peace, prayer and art) with which to teach his people.

The Beehive

Beehive Reception Hall. Artist John Drawbridge created the mural in 1973. It is made up of painted aluminium strips and provides a shifting wall of colour for viewers moving across the hall. View as panorama.

The 'Beehive' is the most recognisable building in the parliamentary complex. It is here that many government ministers have their offices, as well as the Prime Minister and the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. There is a host of meeting spaces, MPs' and other dining rooms, bars and lounges, and television and radio interview rooms. On the two lower floors are large reception areas.

Everyone knew the old buildings were cramped earthquake risks by the 1960s, but whether to knock them down, finish them or remodel was the million dollar question. The issue was so contentious that an outsider, British architect Sir Basil Spence, was brought in. Keep the existing buildings and leave them alone, Spence said – finishing such an old design went against modern-day architectural thinking. Then he quickly sketched out his startling 'Beehive' for housing the executive and Bellamy's. The name came from a box of 'Beehive' brand matches he had been given, and despite official misgivings, it stuck. Bryant and May later made special 'Beehive' matchboxes for sale to MPs.

Whipped up in a flash

Spence was rumoured to have whipped up his design for the Beehive on the back of a napkin during dinner with the Prime Minister in 1964. However it came about, the rough design got a mixed reception when it was unveiled in the House in August 1964. Basil Arthur said it was 'a shocker and should be scrapped', but Labour leader Arnold Nordmeyer praised it. Both parties hoped that a new building might 'become a source of national pride and international interest'. The Government Architect who got the job of turning Spence's sketch into something practical may have been less happy; it was not easy to make efficient use of a circular design with a central 'drum' core, and today, strangers to the Beehive easily lose their bearings.

Next: Doing up the House >