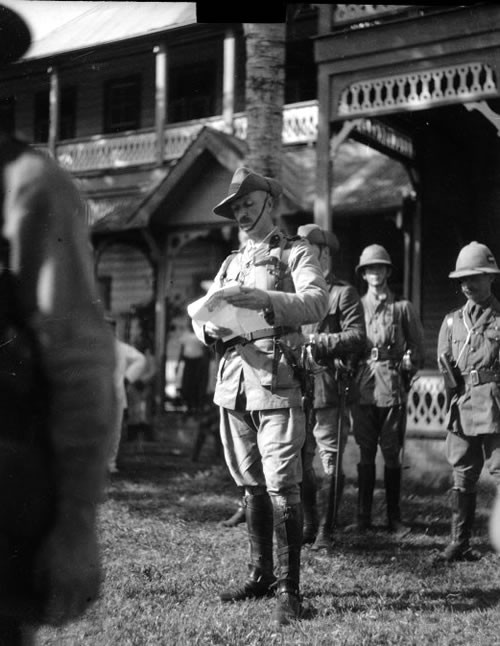

Administrator of Samoa, Colonel Robert Logan, reading a Proclamation of occupation at the flag-raising ceremony in Apia on 30 August 1914 (31 August Eastern time). This was the morning after the occupation of German Samoa by the New Zealand Expeditionary Force.

This extract about Logan's time in German Samoa is from his Dictionary of New Zealand Biography essay by Doug Munro:

He held this position [Administrator of Samoa] throughout the war, by 1918 governing some 38,000 Samoans and another 1,500 Europeans, of whom over one-third were Germans.

Logan was given wide latitude in his new role; he was bound only by the rules of war and, more specifically, the 1907 Hague agreement on occupied territories. After 14 years of German rule Samoa had a thriving plantation economy and political stability, and it made sense to govern his inheritance much as he found it. Although most German officials were dismissed and replaced by New Zealanders, Samoa was administered along existing lines in so far as the exigencies of war allowed. German trade and plantations were permitted to continue largely unimpeded with the proviso that external trade in plantation produce be conducted with Allied or neutral countries. In 1916, however, when it became evident that German firms were still trading with Germany, they were liquidated and placed under New Zealand receivership. The repercussions of this move were considerable: by far the largest of these firms, Deutsche Handels- und Plantagen-Gesellschaft der Südsee-Inseln, financed many smaller planters, who mostly went bankrupt; a cloud of uncertainty descended over Samoa's economic future.

Another cause of economic uncertainty and planter disaffection was more of Logan's making. Most of the plantations depended on indentured Chinese labourers. There were 2,184 in Samoa in 1914 and soon after Logan's arrival they mounted a protest against being short-rationed. The uprising was promptly suppressed and so alarmed was Logan about this 'menace to the European population' that German planters were permitted to carry firearms for protection. Such was his hostility towards Chinese that in 1915 he refused to extend the Chinese labourers' contracts and, despite shipping difficulties and the complaints of planters, he arranged for them to be progressively repatriated without replacement. On the other hand, Logan unilaterally extended the contracts of about 870 Melanesian plantation workers in Western Samoa. Logan's marked antipathy towards Chinese was also based on his conviction that the Samoans deeply resented their presence, and especially the incidence of Chinese cohabitation with Samoan women. In the interests of keeping the Samoan race 'pure', he severely curtailed the civil liberties of the Chinese, taking tough measures to prevent cohabitation or even a Chinese entering a Samoan house.

In the sphere of Samoan affairs Logan was generally content to follow existing German practice. His policy was that Samoan, not European, rights were paramount. Although he lacked his German predecessors' deep knowledge of local custom, and remained somewhat aloof in his relations with Samoan chiefs, native affairs were kept on an even keel, if only by default. One discernible result was a surreptitious revival of some of the practices that the Germans had forbidden the Samoans, such as that of boycotting unpopular local traders. By 1918 Logan was complacently confident that he had won the hearts and minds of the Samoan people in favour of continued empire rule.

Community contributions