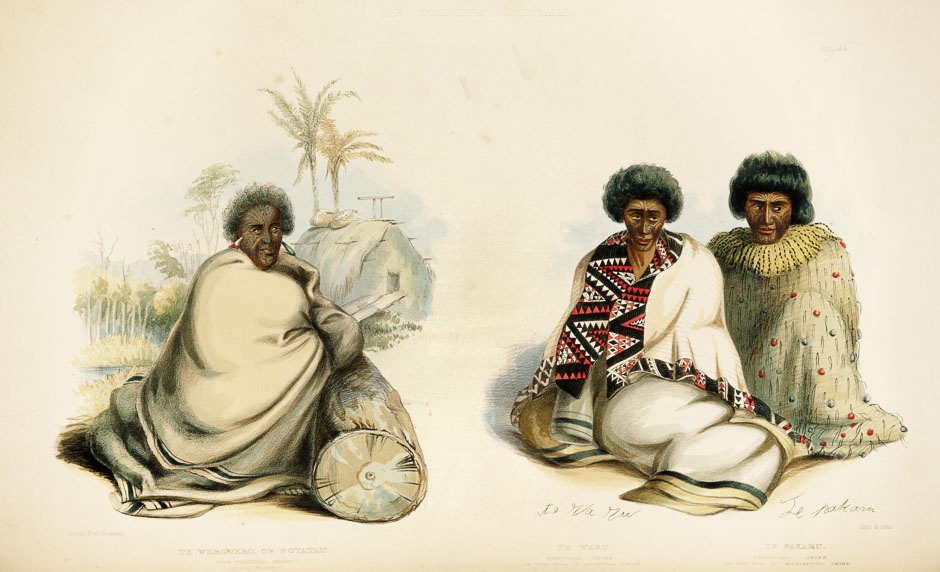

In this 1847 painting by George Angas, Pōtatau is wrapped in a blanket and seated beside a log. On the right are Te Waru, principal chief of Ngāti Apakura, and Te Pakaru, principal chief of Ngāti Maniapoto. All three men have full moko.

The first part of Te Wherowhero’s adult life was spent almost constantly at war as his Waikato tribe drove Te Rauparaha’s Ngāti Toa out of its Kāwhia homeland, defended its own land against Northland’s Ngāpuhi, and made repeated attacks on the Taranaki tribes.

Te Wherowhero refused to sign the Treaty of Waitangi, but he did deal with the colonial government. He sold land to the Crown and, in 1849, signed an agreement to provide military protection for Auckland. He advised Governors George Grey and Thomas Gore Browne, while protesting strongly against a British Colonial Office plan to put all uncultivated land into Crown ownership.

In the 1850s, Te Wherowhero emerged as a popular candidate in the move to appoint a Māori king who would unite the tribes, protect land from further sales and make laws for Māori. Te Wherowhero became Māori King in 1858. Though he didn’t see his kingship as a direct challenge to the authority of the Queen, it was seen that way by both the colonial authorities and some of his supporters. He died after only two years as King and was succeeded by his son, Tāwhiao.

Community contributions