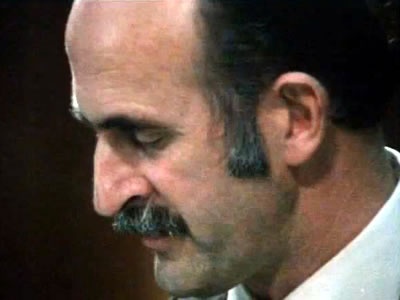

Ron Chippindale, the chief inspector of air accidents, at the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Erebus disaster.

The accident investigation and Chippindale’s reports

After the site investigation in Antarctica was complete Ron Chippindale and his investigators returned to New Zealand to continue their enquiries. This included checking the personnel records of the crew, and studying weather conditions at the time of the crash and other factors that might have contributed to the accident. Chippindale's enquiries also took him to the United States and the United Kingdom from late December to early January. He visited, among others, the manufacturers of parts of the aircraft and the scientists who had analysed the digital flight data recorder (DFDR) and cockpit voice recorder (CVR).

On 4 March 1980 the interim accident report was sent to parties whom Chippindale considered might bear 'some degree of responsibility for the accident'. These parties were the legal representatives of the estates of the pilot and co-pilot of Flight TE901, Air New Zealand and the Civil Aviation Division (CAD) of the Ministry of Transport. They were given 90 days to comment on the report before it was finalised.

At the time Chippindale refused to reveal who had been sent the interim report, advising that to do so would indicate the report's findings. But it soon became clear who had not received it - including the aircraft's manufacturers, McDonnell Douglas - and reports followed that a fault with the aircraft had been eliminated as a cause. The Opposition Labour Party, a consortium representing the estates of deceased passengers, and the New Zealand Airline Pilots Association (NZALPA) were among those demanding to see the report. NZALPA eventually obtained a copy of report from the pilot and co-pilot's legal representatives and learnt that the interim report blamed the accident on pilot error.

Calls for a public inquiry, which had begun shortly after the accident, continued amid the controversy over who had received Chippindale's interim report. On 6 March the Attorney-General, Jim McLay, requested a copy of the report to help him determine if a public inquiry should be held. Two days later he announced that a Royal Commission of Inquiry would be asked to investigate the 'place, time, causes, and circumstances of the accident, together with any other matters that might involve the public or civil aviation safety'.

He denied that the contents of the report were behind his decision, arguing that there was no question that there should be an inquiry into an 'accident of such magnitude'. On 21 April Justice Peter Mahon was appointed to conduct the inquiry.

A number of parties, including Mahon, the consortium, NZALPA and Air New Zealand, protested against the planned release of Chippindale's final report in advance of these hearings. They argued that all of the events related to the accident would be laid out at the Inquiry and that it was here that the findings of the report could be suitably cross-examined. But the government went ahead with the public release of the report at midnight on 19 June.

In the days prior to the release Chippindale advised the media that he had had difficulty finding 'the ultimate cause'. He explained that what he had said in the report was what he thought was the 'probable cause - the last thing that made the accident inevitable', but that there were other factors leading up to the accident.

These other factors, outlined in the conclusions section of Chippindale's report, included 'omissions and inaccuracies' in the route qualification briefing - in particular that the briefing may have given a misleading impression of the route - and the fact that the route was changed after the briefing. Criticism was directed at Air New Zealand and CAD for these and other failures. But the probable cause Chippindale referred to was:

The decision of the captain to continue a flight at low level toward an area of poor surface and horizon definition when the crew was not certain of their position and the subsequently inability to detect the rising terrain which intercepted the aircraft's flight path.

Chippindale concluded that the flight would have proceeded safely had the pilot not descended below the minimum safe altitudes specified by CAD and Air New Zealand.

The criticisms levelled at Air New Zealand and CAD were reported in media outlets in the hours and days that followed. But the focus, and the headlines, went on Chippindale's 'probable cause' of pilot error.

Next page: The Inquiry and Mahon's report

Further information

- History of air accident investigation (NZALPA's Erebus website)

- Chippindale report (NZALPA's Erebus website)

Community contributions