Click on images for enlargements and sources

The impact of design and technology on Wellington café culture, from the 1930s milk bar to the 1960s coffee bar

by Gábor Tóth

The first milk bars

Although Wellington's first restaurants opened in the nineteenth century, the mid 1930s saw the emergence of a different type of establishment, the milk bar, which in many ways was the forerunner to the modern café. This essay considers how design and technology influenced the milk bar and later, the café.

Building permit records reveal that the first Wellington milk bar opened in 1936 at 64 Willis Street. Known as the Black and White, it was owned by Greek immigrant, Mr D. Pagonis. Within a year it had been joined by the Milky Way (4 Manners Street), the Popular Milk Bar (13 Courtenay Place), the Rose (222 Lambton Quay), and the Golden Gate (78 Courtenay Place). The Tip Top dairy company operated at least four milk bars in the central city, and the Opera House also had a milk bar.

Changes in layout

The internal layout was quite different from restaurants, where tables were arranged in rows or at regular intervals. Milk bars were often fitted into the ground floor of long, narrow Victorian or Edwardian buildings. The area at the rear, once kitchen space, could now be used for customer seating. Individual booths began to appear, giving greater privacy for patrons. But the most important feature was the bar itself. This generally stretched for almost the entire length of the establishment, replicating the classic American public bar which Wellingtonians would have been familiar with through exposure to Hollywood films.

New construction materials

While the Art Deco and Streamlined Moderne styles had only limited impact on the construction of new buildings in Wellington, they were influential in commercial interior fit-outs. Products such as stainless steel and plastics were now available to architects; one new material was a cladding sold in New Zealand under the brand name of Vitrolite. It was a pigmented structural glass which could be sculpted, cut, laminated, curved, coloured and illuminated. The clean look of Vitrolite and the ease with which it could be hung meant that it was often used for 'modernising' an existing building.

It was also an inexpensive substitute for marble counter tops, table tops and rest-room partitions, and had hygienic qualities unmatched by wood. Initially only black and white Vitrolite was available, but soon there was a full colour range. The lavish use of Vitrolite in the Black and White gave that milk bar its name. Large panels of black and white Vitrolite sheeting decorated the bar, while walls were clad in a combination of Vitrolite and heavy sheets of mirrored glass.

Milkshake machines

Patrons sitting at the bar could watch milkshakes being made in machines almost certainly manufactured by US firm Hamilton Beach, which pioneered the milkshake machine in 1911. By the early 1930s, the company had developed and patented the multiple spindle machines, which were commonplace throughout New Zealand until the 1970s.

Espresso machines

After 1938 milk bars spread to the suburbs, and no more opened in the central city until 1958. However, in the early fifties cafés started to emerge. They introduced Wellingtonians to espresso coffee and the espresso machine. Descriptions of the hissing, spitting contraptions of the fifties suggest that espresso machines similar to that patented by Italian Luigi Bezzara in 1901 were the first to appear in Wellington's cafés. They featured a tall cylindrical boiling chamber which had to be of a substantial size to create the required pressure. Excess pressure could cause a blow-out, or in extreme cases, a boiler explosion. There is some indication that early cafés were required to obtain insurance to cover damage or injury.

In 1938 the Italian company, Cremonesi, revolutionised the process of espresso making. A hand-operated (and later electrically-powered) piston was used to create a far higher pressure while the temperature of the water was held just below boiling point. This ensured that superheated water would not burn the coffee, producing a bitter brew. These machines gradually began to arrive in New Zealand during the 1950s. They were still expensive and temperamental, and few people had the necessary skills required to maintain them. Parts became almost impossible to obtain when the Labour Government's 'black budget' of 1958 increased import restrictions. Gradually simpler styles of coffee (such as Cona) took the place of espresso.

Café design

The interior design of early cafés, like that of milk bars, was innovative. Formica came to dominate: it offered a hard-wearing surface and was available in a huge range of colours at low cost. For those cafés that could afford the expense, fine wood veneers were used. Two cafés in particular reached a standard of interior design which would have equalled any in Europe at the time: Harry Seresin's Coffee Gallery above the bookshop run by Roy Parsons in Massey House, Lambton Quay, and Suzy's Coffee Lounge in Willis Street.

Harry Seresin's Coffee Gallery

Massey House and the café-bookshop within it were designed in 1952 by Austrian émigré, Ernst Plischke, though the building itself did not open until 1957. It was the first time in Wellington that the 'International Style' had been seen on such a large scale. The main door opened through massive panes of glass which reached the full height of the ground floor level in single sheets. The café was on a mezzanine level, reached by a 'floating' stairway. Patrons sat surrounded by panels of rimu and sycamore veneer, and at the northern end of the café could look out over the bookshop and into Lambton Quay. The café is now about half its original size and the view to the Quay is now obscured by additional book shelving, but its interior remains essentially original, testimony to the quality of its classic 'early-modern' design.

Suzy's Coffee Lounge

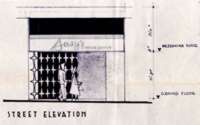

Suzy's Coffee Lounge, opening in 1964, was designed by another Austrian émigré, Friedrich Eisenhofer, and sported bold primary colours and sharp lines and angles. Unlike Seresin's Coffee Gallery, a sculptured front window screen restricted vision to and from the interior, creating a more intimate atmosphere. Internal screens and modern stained glass windows added to the cosy feeling.

Most cafés, however, did not go to the same trouble or expense to create stylish designs. Many were short-lived affairs where the height of sophistication was a candle stuck into a bottle. This trend, in combination with the use of scrim as a wall covering, led to a tightening up of fire regulations for café owners.

From the early 1970s, cafés in Wellington began to disappear. It was only from the late 1980s that Wellington saw the rebirth of its café culture, and with it, the emergence of a true vernacular style of Wellington café. Today, these establishments display some of the most innovative commercial interior fit-outs ever seen in the city.