Radio contact lost with Flight TE901

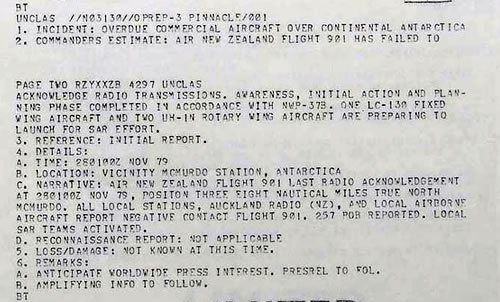

This US Navy situation report shows their attempts to contact Flight TE901 and planned search and rescue efforts after contact was lost with the aircraft.

Out of touch

Morrie Davis

Shortly after Mac Centre and Oceanic Control agreed to upgrade the phase to ‘alert’, the news that TE901 had been out of radio contact for some time was conveyed to the airline's Chief Executive, Morrie Davis. He was at Wellington Golf Club at Heretaunga, having participated in a warm-up event for the Air New Zealand-Shell Open Golf Championship, which was to begin the following day.

The crash of Air New Zealand's Antarctic Flight TE901 happened so quickly that the crew had no opportunity to react, let alone radio the ground with any sign of distress. But staff at Williams Field 'Ice Tower' in Antarctica soon grew concerned. They had expected to sight the aircraft overhead their location within minutes of a transmission from TE901 at 12.45 p.m. (NZST)*. In this message the crew advised they were at 6000 ft (1830 m) in the course of descending to 2000ft (610 m) and that they were still operating in visual meterological conditions (VMC).

When it failed to appear, without radioing a change in heading, Ice Tower and staff at Mac Centre, the United States Navy's air traffic control centre at McMurdo Station, initiated a series of radio calls to the aircraft. They had had problems communicating with TE901 on VHF earlier in the flight, but had been able to get through on HF. This time, after several calls on both frequencies, there was still no response. Mac Centre then asked all local stations, local aircraft, and the air traffic control centre in Auckland, Oceanic Control, to radio the aircraft. No one received a response.

Maria Collins

Maria Collins, the wife of TE901's Captain, Jim Collins, first learnt that something was wrong at around 6.45 p.m. (NZDT), when Captain David Eden, Air New Zealand's director of flight operations, phoned to let her know that Jim had been out of radio contact for several hours. While he said she shouldn't be concerned, he also suggested that she get someone to keep her company. Anne Cassin, the wife of one of the first officers on the flight, Greg Cassin, received a similar phone call from David Eden at around 7 p.m.

By 2 p.m. (NZST) the flight had been radio silent for over an hour - and there was an accepted procedure that required aircraft to report to Mac Centre at intervals of not less than 30 minutes. Mac Centre informed Air New Zealand headquarters in Auckland and advised them that search and rescue aircraft had been activated. Less than an hour later, at 3.41 (NZDT), Mac Centre and Oceanic Control agreed to declare an ‘uncertainty phase'. This was later upgraded to ‘alert' at 4.27 (NZDT), and to ‘distress' at 5.55 (NZDT).

At 4.16 p.m. (NZST) a US Navy Lockheed LC-130 Hercules, XD-01, left McMurdo to search TE901's last known coordinates. Twelve minutes later, a US Air Force Lockheed C-141A Starlifter that had travelled to Antarctica approximately 50 minutes behind TE901 left for Christchurch to search along the aircraft's proposed flight track. At 5.21 (NZST) a UH-1N helicopter, Gentle 17, was dispatched to search the Dry Valleys. Five minutes later another helicopter, Gentle 14, was dispatched to search Ross Island.

*On the day of the Erebus disaster there was a one-hour time difference between New Zealand and McMurdo Station. McMurdo Station was operating under New Zealand Standard Time (NZST) while New Zealand was operating under daylight saving or New Zealand Daylight Time (NZDT). Scott Base and McMurdo Station did not begin observing daylight saving until 1992/93.

Next page: Overdue

Credit

Image: Archives New Zealand, Te Rua Mahara o te Kawanatanga, Christchurch Regional Office Reference: CAHU CH282 3-28 p1. US Navy SITREP [SITuation REPort] from 28 November 1979.

Facebook

Facebook Google

Google Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Twitter

Twitter

Community contributions