‘Surely the best of all the Maori stories’ is how Margaret Orbell, the editor of the magazine Te Ao Hou, described the tale of the impetuous 17th-century lovers Ponga and Puhihuia. The story describes an illicit romance taking place in a world of desperate canoe voyages, flamboyant dances, cunning deception and hand-to-hand combat, set around the Manukau Harbour. It is rich in song-poetry, oratory, archaic custom and tribal history, and its Māori-language version is a storehouse of pre-European terms and expressions.

John White

So it's rather surprising that today Ponga and Puhihuia are not nearly as well known as other Māori folk heroes such as Hinemoa and Tūtānekai, Hatupatu, Rona and Paikea. This may be because their story was first written down and translated by the 19th-century folklorist John White. He acquired a reputation for rewriting stories provided by his Māori informants, merging several versions into one and at times supplementing them with his own inventions.

White arrived in New Zealand with his family in 1835, aged nine. They settled on the south side of the Hokianga Harbour, and John spent much of his youth asking local Māori about their customs, history and traditional stories. In 1850 he sent samples of waiata to Governor Sir George Grey, who engaged White as his translator and personal secretary. When Grey's collection of Māori oral traditions, Nga mahinga a nga tupuna, was published in 1854, it included a brief version of 'Te Ponga raua ko Puhihuia', the story's first appearance in print. It seems likely that White originally heard this story during one of his many trips to the Manukau area and supplied it to Grey for publication.

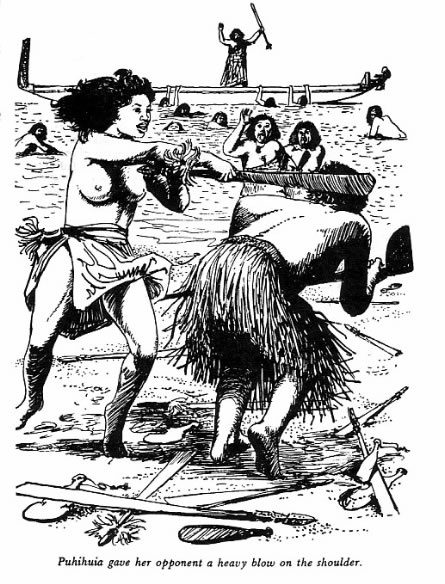

In 1879 White was commissioned by the government to edit The ancient history of the Maori, a collection of oral traditions. Volume IV of this work gives a longer version of the story of Ponga and Puhihuia, attributed to Ngāti Kahukōkā, the tribe traditionally based at Āwhitu on the Manukau Harbour. Ponga, a young chief of Āwhitu, travels with his companions to visit relatives at Maungawhau (Mt Eden). During the welcoming dances he and Puhihuia, the young daughter of the chief of Maungawhau, fall in love with each other and escape by canoe, pursued by her tribespeople. Puhihuia's mother sends a war party of women to recapture her daughter, but Puhihuia refuses to return home and defeats each of the women in single combat. This convinces her family of her love for Ponga, and peace is made between their two peoples.

Dr Orbell greatly admired White's version of Ponga and Puhihuia's death-defying elopement for 'the intricacy and subtlety of the web of custom and motive which the story reveals, the skill of its telling and the richness of its detail'. Today the story is taught in postgraduate Māori language classes as an outstanding example of early oral literature. Others have accused White of inventing the story. He may have heavily embroidered a version he received from a long line of anonymous Ngāti Kahukōkā storytellers, but, if so, he was simply repeating and adapting the process by which they acquired it. In any case, White deserves praise for preserving a magnificent tale not elsewhere recorded in print.

The fragrant gifts conveyed by Āwhitu's young people to their Maungawhau relatives, their dancing ('so agile that they could move their bodies as though the waist of each were cut in two'), the bravura oratory of the chief of Āwhitu as he risks his people's lives to shelter Puhihuia, and the vividly metaphorical language in which these events are expressed, provide a glimpse of Aotearoa as it was long before the arrival of the musket. The subsequent impact of colonisation disrupted but did not completely sever the chain of oral transmission by which stories like Ponga and Puhihuia's were passed on. We can be grateful for John White's link, however haphazard, self-interested and improperly acknowledged, in that chain.

By Mark Derby

Double-page spread from a version of the story written in blank verse in the style of Henry Longfellow’s 'Hiawatha', and privately published in 1961.

Community contributions