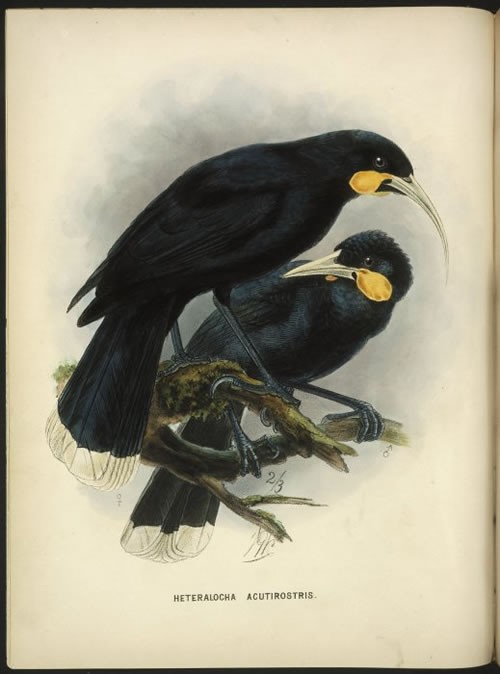

A plate from A history of the birds of New Zealand by Walter Buller, showing a pair of huia perched on a branch, the female (marked with a small female symbol) to the left, the male (marked with a small male symbol) to the right. A Dutch artist, J.G. Keulemans, was responsible for the illustrations in all of Buller's books. His illustrations are remarkably lifelike considering he never stepped foot in New Zealand, and rarely saw living examples of the birds he drew.

A history of the birds

Today many New Zealanders would undoubtedly find Sir Walter Buller's comment that 'the flesh of the pukeko [is equal] to that of the best English game' distasteful. But Buller, the author of A history of the birds of New Zealand, was not out of step with his contemporaries.

At the time his book was first published in the early 1870s legislation focused on protecting introduced species rather than natives. Buller's work was viewed by many of his contemporaries as a record of the country's native birds before they inevitably died out. Criticism levelled at Buller related either to his skills as an ornithologist, or to the favourable treatment he received from the government while preparing his book.

Buller drew up an initial outline for his book in July 1867. At about the same time his ornithological work was subjected to its first critical analysis. A German ornithologist, Otto Finsch, had obtained a copy of an essay Buller had distributed to various institutions in London. Buller had prepared the essay for the New Zealand Exhibition in 1865 but this was the first time it had been made available in print. Finsch, who had 'made a special study of the birds of the Pacific Islands', took issue with some of the new species Buller identified. His attempt to analyse and classify species was at odds with the approach of most contemporary New Zealand scientists, who were prepared to leave this responsibility to the ‘experts' in Europe. Buller fought off the criticism but also realised that for his book to be taken seriously he would have to base himself in London and make use of the superior library and museum facilities there.

Buller didn't revive his book outline until July 1870. By this time Dr James Hector, then 'the key figure in New Zealand science', was less enthusiastic about a proposal he and Buller had worked out in 1867. This entailed Buller donating his specimens (then numbering over 200) to the Colonial Museum, in exchange for the government contributing £300 towards the book's publication. Hector was particularly concerned that Buller's specimens were worth less than they had discussed. Cabinet accepted Hector's recommendation that Buller be required to provide the government with 25 copies of his book and approved the grant. The following year Buller asked Dr Isaac Featherston, who had seconded him to work on the Rangitikei-Manawatu purchase, to support his application for special leave from his position as resident magistrate in Whanganui. Buller was granted 18 months leave on half pay plus a return passage to London, where he arrived in October 1871.

As part of the agreement Buller also negotiated a position as part-time private secretary to Featherston, who was due to be appointed New Zealand's new agent general in London. His salary was to be equivalemt to his total income at Whanganui. This was fuel for the Opposition, who accused the government of patronage. They seized on the fact that the new magistrate at Whanganui was receiving only a third of the £600 Buller was getting while on leave in London, and noted that Buller was earning more in London that he had in Whanganui. Though Buller explained the disparity as a mistake in his estimate of court fees, he was eventually forced to resign his magistrate's position. Featherston was instructed not to employ him as secretary. The Evening Post scornfully reported on the situation on 18 August 1873:

Mr Walter Buller has hitherto been one of Fortune's favourites in the Civil Service – one of those curled darlings who must be provided for at all hazards, and who had only to open his mouth in order to have it filled with plums.

In view of the criticism he had received Buller was no doubt thankful that his book was a critical and commercial success. It was published progressively, the first part on 4 April 1872, the fifth and final part by the end of March 1873. Buller sent the government their 25 copies, proudly noting 'that all but forty of the entire edition of 500 had been subscribed for'. He completed an enlarged second edition in 1888 and a supplement in 1905. He died the following year.

Writing on Buller's legacy in 1989 his biographer, Ross Galbreath, observed that 'All else might be forgotten; but "Buller's Birds", his great volumes, remain admired, coveted, and still consulted'.

Further information:

- Ross Galbreath, Walter Buller: the reluctant conservationist, GP Books, Wellington, 1989

- Biography of Walter Buller (DNZB)

- Buller, Sir Walter Lawry (1966 Encyclopaedia of New Zealand)

- A history of the birds of New Zealand (NZ Electronic Text Centre)

Community contributions