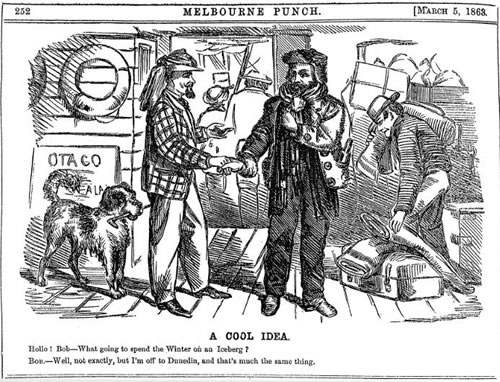

Following the discovery of gold at Gabriels Gully in Otago (1861), thousands of miners left Australia’s main goldfields in Victoria to try their luck in the South Island. Further discoveries were made at Wakamarina in Marlborough (1864) and at Greenstone Creek on the West Coast (1864). Between 1861 and 1867 there were 50,000 new arrivals from Australia. Many left as the rush slowed but over 11,000 stayed. A number of these arrivals became prominent New Zealanders, including future premiers Julius Vogel and Richard Seddon. Strongly independent with a firm sense of democracy, the Australian gold miners had a long-term impact on New Zealand’s political culture.

Some were less desirable additions to the New Zealand population. Richard Burgess and one-time prison mate Henry Garrett were the sort of men some feared would join the mass exodus to the Otago goldfields. St John Branigan, the head of the fledgling Otago police force, warned that such men would be attracted to Otago not just because of the promise of rich pickings from the goldfields but from the pockets of unsuspecting miners. As a recruit from the Victorian police Branigan had 'seen it all before'.

At one point Hokitika was described as ‘a suburb of Melbourne’, such was the level of migration from the Victorian goldfields. Burgess and his associates followed this well-beaten path from Victoria to Otago and then on to the other South Island fields. Upon their release from Dunedin gaol in 1865 Burgess and Kelly headed straight for the West Coast and it was in Hokitika that the final members of the Burgess gang – Levy and Sullivan – were recruited. Burgess had known Levy from his time in Victoria, where Levy worked as a gold buyer and 'fence' (someone who sells stolen goods). Sullivan had also lived in Victoria prior coming to New Zealand.

Community contributions