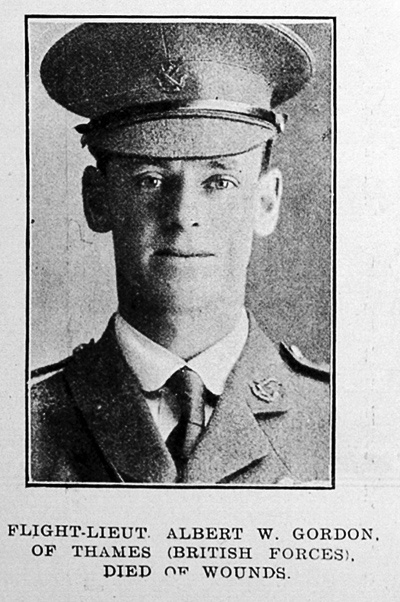

Albert Gordon

Flight-Lieutenant Albert William Gordon was one of more than 700 New Zealanders who joined British or Australian air services during the First World War. Because New Zealand did not have its own air force, they volunteered as ground and aircrew in the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), or Australian Flying Corps (AFC). About half saw operational service – flying scouting missions, and engaging enemy aircraft over the battlefields of Europe and the Middle East – and more than 70 lost their lives.

Gordon trained at the New Zealand Flying School (NZFS) at Kohimarama on Auckland’s Waitematā Harbour, receiving his flying certificate (‘ticket’) in August 1916. The school, partly funded by the British government, contributed 83 pilots to the war effort. After logging between four and eight hours’ flight time in seaplanes around Auckland, Gordon, like many NZFS graduates, travelled to England to complete his training in the RFC. Allied pilots sent from England to the Western Front usually had around 30 hours of flying experience. They were competent flyers but had little idea of how to engage enemy aircraft.

On the evening of 30 July 1917, one week after joining No. 32 Squadron on the Western Front, Gordon and two other pilots took off on a scouting sortie. The following month a newspaper correspondent reported on Gordon’s last flight:

The three friends went out shortly before 7 p.m., and at 6000 ft up, Capt. Coningham recognised, coming through a cloud-bank 1000 ft below, five German aeroplanes, commanded by Wolf, one of the ‘crack’ enemy airmen…. Diving down on the enemy, Capt. Coningham quickly accounted for one of the five, and he fell out of action. As luck would have it, Wells could do nothing because his gun jammed at 6000 ft, so he was completely out of the fight. While Coningham took on one of the enemy, the other four German machines began to mount, and got above him, and very soon Gordon was hit. He was at a disadvantage, inasmuch as he had not previously met a Hun in the air, and did not realise that it was a case then of two against five. There was no means of his receiving the information, as one machine cannot communicate with another. Instead, at the outset, of tackling an enemy machine, he followed Coningham, to join what he took for friends, and the consequence was he was surrounded, while enemy missiles were aimed at him.

Evening Post, 23 October 1917, p. 8

Although Gordon managed to crash-land his crippled plane, the impact broke both his legs. Transferred to a hospital near Étaples, he seemed ‘full of spirit and very happy’ before dying suddenly on 12 August. After receiving news of her son’s death, Gordon’s mother appealed to Minister of Defence, Sir James Allen:

I received your letter today saying no trace of A W Gordon that was reported died of wounds…. I do sincerely hope you will confirm this or let me know otherwise, because Albert sent me a wire saying Hope soon to be in London on the 6th Aug 7 days after he was injured….

On the first anniversary of Gordon’s death, his parents placed a memorial notice on the front page of the Thames Star. This included a poem which expressed the family’s sense of loss:

What happy hours we once enjoyed

How sweet his memory still,

But death has left a vacant place

This world can never fill.

We often think of days gone bye

When we were all together

A shadow o’er our life is cast

Our boy is gone for ever.Thames Star, 12 August 1918, p. 1

Facebook

Facebook Google

Google Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Twitter

Twitter

Community contributions