A European outpost

James Belich in Making Peoples described how in the 18th and 19th centuries, Europe exploded outward in one of the most incredible expansions in human history. This European explosion first impacted on New Zealand in the closing decade of the 18th century when sealers and whalers began to arrive in their hundreds seeking to exploit local resources.

They encountered a Maori world. Contact was regional in its nature; many Maori had no contact with Europeans. Where contact did occur, Europeans had to work out a satisfactory arrangement with Maori, who were often needed to provide local knowledge, food, resources, companionship, labour and, most important of all, guarantee the newcomers' safety. Maori were quick to recognise the economic benefits to be gained in developing a relationship with these newcomers.

Europeans of all descriptions came to New Zealand during this time — Dutch, French, Russian, German, Spanish, Portuguese and British, as well as North Americans.

Much of this contact 'was strained through Sydney first'. Known variously as Botany Bay or Port Jackson, the Australian port became the hub of the South Pacific's whaling and sealing industries and received the bulk of New Zealand's early trade.

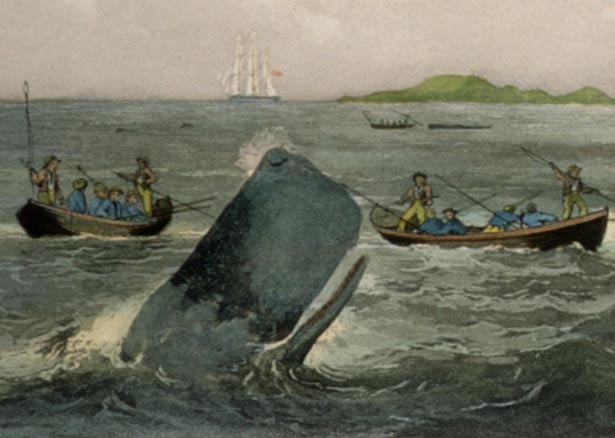

The New Zealand fur seal and the humpback, sperm and southern right whales, which migrated through New Zealand waters on their seasonal journeys to and from Antarctica, proved easy targets for the sealers and whalers who arrived in 1791–2.

Maori and whaling

Some Maori joined whaling vessels as crew and Sydney became the most visited overseas destination for Maori. The whaling ships offered the opportunity to travel and thus the great New Zealand tradition of the 'OE' was born. There were, however, instances of Maori being poorly treated on some of these ships.

Maori also played a major role in shore whaling, many going on to become boat steerers and headsmen, or set up their own stations. In Hawke's Bay the stations depended heavily on Maori labour, making the relationship between Maori and Pakeha whalers one of mutual respect and equality. Prominent Ngati Kurukuru chief Tiakitai had, for example, served as the patron of Morris's Rangaika whaling station until his death in 1845, bringing it under his protection. Maori, in exchange, gained access to goods, money and work.

The importance of Maori patrons diminished as the European population grew. Maori were pushed to the economic and political margins. The war in the Bay of Islands 1845–6 was partly a response to the loss of trade that resulted from the shifting of the capital to Auckland. In January 1847 the house of William Edwards, the owner of the Putotaranui whaling station, a few kilometres south of Rangaika, was burned down, killing his infant son. Edwards believed this was the work of local Maori upset at the Pakeha taking advantage of them.

Further information:

This web feature was written by Steve Watters and produced by the NZHistory team.

The nature and impact of sealing and whaling on New Zealand are explored in the 'Earth, Sea and Sky' section of Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. In particular: