At 12.51 p.m. on 22 February 2011, the Canterbury region was struck by a magnitude 6.3 earthquake. At the time it was still recovering from the effects of a 7.1-magnitude earthquake on 4 September 2010. Though smaller than the first quake, and technically part of its aftershock sequence, the February earthquake was more destructive. It caused greater devastation in most parts of the region and 185 lives were lost.

12.51 p.m.

Most Cantabrians were away from their homes when the 6.3-magnitude earthquake struck at 12.51 p.m. on 22 February 2011. It was the middle of a working day and many people were at school or work, having lunch or running errands.

The September quake had occurred in the early hours of the morning with family generally close at hand. This time it was often colleagues, classmates or complete strangers who comforted and helped each other during the initial eight-second jolt and the aftershocks that followed. Kris, who was in the Forsyth Barr building during the quake, recalls working with colleagues to try to get out, only to discover that the building’s stairwell had collapsed:

A group of people from my office banded together. We helped one colleague search for her cellphone, which she had lost in the panic of diving to get under her desk. Then we made our way to one of the stairwells and set off for the ground. The emergency lighting had failed in the stairwell, so we could barely see the steps in front of us. As we slowly went down the stairs between our 15th floor and the 14th floor, one of my colleagues remembered he had a torch in his pocket. (I guess he grabbed this from his office, and then forgot about it.) He flicked the torch on, and at the same time Paul, who was leading us down the stairs, turned around and told us that we needed to go back up and try to find another way down. The stairwell had collapsed immediately below the landing at the 14th floor. We did not realise at the time how badly the stairwells had failed, but it was obvious that we could not get down.

http://www.quakestories.govt.nz/183/story/

Once assured of their own safety, most people’s thoughts turned immediately to friends and family – especially children. Schools had been holding regular earthquake drills since the September quake. Even preschool children were familiar with a drill known as ‘the turtle’. But of course parents wanted to reach their children’s schools as quickly as possible. Frances describes her journey and what she found when she arrived:

I knew that the kids were no doubt safe at school (they do a lot of earthquake drills) but [felt] that we should go and get them anyway. Then a large aftershock hit and the entire block of houses leapt and bucked in the air and people were screaming in fear and anger.

I grabbed my handbag, mobile phone and keys (running quickly inside to get these, then straight out again) and we [my mother-in-law and I] started walking to school (I could already see that driving would be a stupid idea, as there were cars everywhere). Our 15 minute walk took us past the Stanmore Road shops, and I tried not to get emotional about all the collapsed buildings and the people desperately digging in the rubble to get to the people buried underneath.

Everyone was out on the streets and everyone asked the same question of each other – ‘Are you alright?’

I got to the school and was impressed that there was a strict emergency plan in place – staff on each gate issuing instructions. All the children were sitting in the middle of the open air playground area, many crying, all looking very scared. Teachers were sitting and cuddling several children at once, trying to comfort them. The air was thick with dust from collapsed buildings and smoke from fires. A burst water pipe had cracked through the surface of the basketball courts and water was seeping everywhere. It was like a war zone.

I saw my kids – they were looking incredibly traumatised and had been crying a lot. They clung to me and we sat down at the edge of the playground to wait for my husband, who’d texted me to say he’d meet me there. One of my best friend’s daughters was hysterical, so I grabbed her too and we had a big group hug for about half an hour, trying to calm down, trying to make light of the bigger aftershocks, which were rumbling through on average every five minutes.

http://www.quakestories.govt.nz/105/story/

The Turtle

‘Turtle Safe’ is an earthquake safety resource aimed at preschool children which encourages them to act like a turtle during an earthquake – drop to the ground, cover your head and hold on to something if you can. It was originally created by Auckland City Council in the 1990s or 2000s. After the February 2011 earthquake, Auckland Council and the Ministry of Civil Defence and Emergency Management jointly reissued the resource as a DVD.

A number of schools found they couldn’t follow the emergency procedures they had practised because many students were outside the classroom having lunch. Despite this complication, and hazards that included unsafe and collapsing buildings, no child was seriously injured or killed at a school.

Some parents had more difficulty reaching their children. A number of high schools had released their students at lunchtime to allow teachers to attend a union meeting. By 12.51 many were at friend’s houses, shops or food outlets. Drew was at the Tower Junction shopping centre on Blenheim Rd when the earthquake struck:

We had finished school early that day. My friend Phoebe and I were walking back to Phoebe’s parents’ work. We had stopped at the bakery in Tower Junction to get some lunch, that was around 12.40 p.m. Once we got outside to sit down to eat it was about 12.50 p.m. Once 12.51 p.m. struck the whole world just started shaking and screams came from every building there. Me and Phoebe just stood there in shock wondering what to do next. After the shaking had stopped we ran through the parking lot to find [Phoebe’s] parents who were working close by to where we were. Car alarms were going off and that was all you could hear. The streets were filled with liquefaction and dazed people. All the cellphone lines were out of action so it was hard to contact my family. Six hours later my dad rocked up to get me.

http://www.quakestories.govt.nz/247/story/

While most people sought out friends and family after they had helped those around them, some stayed where they were for many hours providing assistance. Many who encountered the worst scenes in the CBD, at the Canterbury Television (CTV) and Pyne Gould Corporation (PGC) buildings, did whatever they could. In his contribution to QuakeStories, Mike recalls taking part in the rescue effort at the CTV site:

Our assembly point was Latimer Square – so we had to walk past the CTV site.

I remember holding someone’s hand and asking someone else to hold this person’s hand – and the next thing I recall is standing on the rubble of the CTV site – one of about 8 or 9 people who were helping to lead people down with various injuries from what appeared to be a hole at the top of the rubble…

I know I was at the site for about 7 hours – but it seemed like 10 minutes – and much of the afternoon is lost.

I see pictures of myself at the site in the paper the next day – and I can’t recall what I was doing at that point.

I hadn’t heard from my kids, or their mum, or my partner or anyone – then suddenly – about 30 txts and missed calls appear on my phone.

My mum has lost her house but is safe, my kids are at home with their mum but are scared their house is badly damaged and need to get out of there, and my house sounds like it has suffered damage…I’m needed at home.

I think – this will be the most difficult decision I have or will ever make in my life … walking away from the CTV site. The police, Fire and ambulance service and USAR were well in control and the rescue was coordinated and moving quickly … so, I knew I wasn’t needed … but, deciding it was time to go home and leave all of those brave people and not help anymore … was heartbreaking.

http://www.quakestories.govt.nz/159/story/

Those trained and equipped to handle such emergencies were assisted in the immediate aftermath of the quake not only by volunteers of all descriptions but also by the fortuitous presence of a large number of New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF) personnel who were in the city to conduct a training exercise. The military helped police establish and maintain a cordon around the CBD and, in the following days, moved out to suburban areas to reassure the public. Naval personnel who were in Lyttelton at the time of the quake helped the community in a number of ways, dishing up 1000 meals and providing emergency accommodation on HMNZS Canterbury.

Despite the valuable contribution of volunteers and the NZDF, there was enormous pressure on the city’s dedicated emergency services – Police, Fire Service and St John Ambulance – in the immediate aftermath of the main shock. Each organisation was flooded with 111 calls for help from the CBD and suburbs on top of business as usual – and staff also needed to look to their own families. While making a number of recommendations for each service, an independent review of Civil Defence’s Emergency Management response concluded that over the first 24 hours they had coped in a ‘commendable and on many occasions courageous’ fashion with demands that far outstripped their resources.

Felt reports

The epicentre of the 22 February earthquake was within 10 km of Christchurch city, but it was felt strongly throughout Canterbury. Geonet, the country’s geological hazard monitoring system, received thousands of ‘felt reports’. While most came from the east coast of the South Island, there were a number from the west coast and the lower two-thirds of the North Island.

Contributors to QuakeStories describe what they felt and heard:

It felt as though something had taken hold of the building and was shaking it furiously from side to side and up and down.... It was like some giant or maybe King Kong taking hold of the building and shaking it.

http://www.quakestories.govt.nz/98/story/The world seemed to pick up the building I was in and throw it around...

http://www.quakestories.govt.nz/187/story/We could hear the almighty rumble as other buildings collapsed, and dust was everywhere. It was like I imagine the Blitz was like...

http://www.quakestories.govt.nz/394/story/The sound was awful, a loud noise like a huge aeroplane landing...

http://www.quakestories.govt.nz/488/story/The noise was so intense, like a train coming through the building.

http://www.quakestories.govt.nz/446/story/Within seconds I found myself huddled against the retaining wall in my back garden, listening to the sounds of walls collapsing, breaking glass and the ominous boom, boom, boom as huge boulders came bouncing down the hillsides around me. After the incredible noise, silence. Deafening silence, no birds, no movement.

http://www.quakestories.govt.nz/53/story/

Aftershocks

By the time of the February quake, Canterbury residents had experienced thousands of low-magnitude aftershocks since September 2010. Some contributors to QuakeStories initially thought this was yet another one:

At first I thought that it was just another aftershock, but when the power went out and the room felt like someone had picked it up and was bouncing it around, I realized that I needed to get under my desk, which was unfortunately a very thick wooden one. The shaking got worse but eventually it stopped. I thought that that aftershock had been a particularly powerful one.

http://www.quakestories.govt.nz/301/story/We’d had a couple of small seismic rumbles that day; very tiny aftershocks from last September’s Darfield earthquake, or so I thought. As I sat on the sofa, my sensitive ears detected those deepest of bass notes that announce another aftershock, but within less than a second the vibrations had undergone a massive crescendo, and the house began roaring around me. I put my feet on the floor and braced my arms as the house was violently shaken, and this time things were different. It wasn’t like riding big waves, or being blown around in a high wind. It was the sharpest, most violent kind of shaking; as though the house sat on some giant mechanism of limitless force that was snapping it back and forth, up and down, however it liked. That the house stood up to it at all was pretty incredible. It seemed like just the shaking itself was physically painful, and the noise was incredible, deafening, like nothing I’ve heard or could compare it to.

http://www.quakestories.govt.nz/100/story/

The February quake was powerful enough that while classified as an aftershock of the September quake, it generated its own aftershocks, including a magnitude 5.8 at 1.04 p.m. and a magnitude 5.9 at 2.50 p.m.

The aftershocks placed still more stress on the city’s residents, buildings and infrastructure. Hebe, who was at Unlimited Paenga Tawhiti school in a multi-storey building in Cashel Mall at the time of the quake, recalled one of the big aftershocks:

I think it was around this point that one of the big aftershocks hit, my best friend and I must have looked terrified, for the office lady let us hide under her desk…. We sat quivering under the desk for some time, the office ladies were very nice, but frightened also.

http://www.quakestories.govt.nz/126/story/

The aftershocks were particularly dangerous for people who were trapped under debris or in buildings, and for those who were trying to rescue them. Lyn Reid, who was injured in the earthquake and remained trapped in the Press building for more than three hours, feared that it would collapse:

With the aftershocks I thought, Here we go. You just think of the [Twin] Towers and you think that is going to happen.

Her fear of the aftershocks persisted after she was rescued and admitted to a ward on an upper floor of Christchurch Hospital:

I was screaming and crying, the building was rocking around so much and I said, ‘Just get me out of here please.’ So within the hour I was out of there. I just packed my things up, came back and the ambulance was waiting for me. In Burwood Hospital I was on a single level and I had my own room. It was heavenly. I had a television on the wall and could see outside. I did not need psychological help. I wasn’t traumatised. I just didn’t like the feeling of the aftershocks. [1]

Most emergency services workers who wrote about the quake did not mention the aftershocks. Perhaps they felt as Urban Search and Rescue (USAR) squad leader Mike Carter did. In an interview published in the New Zealand Herald two days after the quake, Carter noted that ‘The job had its dangers, and it was scary being trapped inside a collapsed building when the aftershocks struck’ – but ‘he preferred to focus on the potential rewards, rather than the risks of what they were doing’. [2]

The aftershocks were far from over – there were thousands more to come. On 14 June 2011 the city experienced a series of strong aftershocks, including a magnitude 5.6 and a 6.3. A further series hit the region on 23 December 2011. Both events caused further damage and disrupted the city’s recovery.

Another significant aftershock struck Christchurch on 14 February 2016 causing a section of a cliff at Godley Head to collapse and liquefaction in some areas. The magnitude 5.7 quake came just a few days before the fifth anniversary of the February 2011 earthquake.

Lives lost

One hundred and eighty five people died as a result of the 22 February earthquake. One hundred and fifteen died in the CTV building, 18 in the PGC building, 36 in the central city (including eight on buses), and 12 in the suburbs. The Chief Coroner determined that another four deaths were directly associated with the earthquake. (A complete list of the deceased can be found on the New Zealand Police website.)

Most of those who died were Christchurch or Canterbury residents with ties to the local community. Their loss was felt not only by their family and friends, but by many others in the region who knew them or their family. In a blog written two days after the quake, Jennifer reflected on the likelihood she would know someone who had died:

I’ve heard (either directly or indirectly) from all my close friends and most of my workmates now, so know they’re ok, but I also know the chances are, in a city of only half a million, that all of us will end up knowing someone who is a victim. And probably everyone in our tiny country will know someone who’s lost someone – already I’ve heard that the owners of a shop near my brother’s have lost their son.

http://www.quakestories.govt.nz/185/story/

Some of each individual’s many connections could be seen in the death notices placed in the Press in the days after the earthquake, and the memorial notices published on the first anniversary of the quake. The Press inserted a notice for the colleague they had lost:

In loving memory Adrienne Lindsay (Ady)

A special friend and loyal member of our team

Loved and sorely missed by her friends and colleagues at The Press. [3]

A significant proportion of those who died were visitors to the region, some of whom had only been in New Zealand a few days. Many were students learning English at King’s Education in the CTV building. People from more than 20 countries died in the earthquake.

Initially some hope was held for those trapped in the CTV and PGC buildings, and family members and friends gathered nearby, some buoyed by text messages sent by their loved ones after the quake or reports from those who’d escaped or been rescued from the buildings. Next of kin based overseas had to rely on second-hand information. Kuniaki Kawahata was deputy director of Toyama College of Foreign Languages, which had students and staff at King’s Education. His daughter was among them:

I drove home and I was shouting my daughter’s name. In our language we think language has some sort of spiritual power so I yelled my daughter’s name so it might reach my daughter who was 9000 km away. I did that several times. [4]

Unfortunately for those waiting at the scene and elsewhere, no more survivors were found after the first 24 hours. Search and rescue efforts were eventually scaled back and replaced by the search for and recovery of remains.

A number of groups assisted with this grim and difficult task at these buildings and elsewhere. They included national and international Urban Search and Rescue (USAR) teams, many of whom did not reach the city until after all the successful rescues had been completed. Thanks to the efforts of these groups and the New Zealand Police, other disaster victim identification (DVI) specialists and Coronial Services, 181 of the 185 victims were eventually identified. The remains of the four ‘unfound’ victims were interred at a special site in Avonhead Park Cemetery in February 2012.

Some families voiced criticism of the time it took to name victims. Those involved in the process explained that they were working as quickly as they could while following international DVI standards. In March 2011, Police Superintendent Sam Hoyle asked for ‘patience and understanding’:

We are acutely aware that families want their loved ones returned, particularly our guests from overseas, and our teams are working flat out to achieve this.

However international experience from events such as the Boxing Day Tsunami and the Victoria bush fires has shown it can be months before all identities are confirmed. In exceptional cases it has taken years to identify all the victims of mass casualty events.

This is painstaking, exacting work and the reality is very different from how it looks in television programmes such as CSI. You don’t get DNA matches in seconds at the push of a button – it takes time.

We are following international best practice standards and have some of the most experienced DVI specialists in the world working with us.

The focus is to make accurate identifications. We are not going to rush this process and risk causing further pain to grieving families by making a mistake. If we make a mistake we create uncertainty and doubt for everyone. We can't make it better for the families but we can certainly make it worse for them if we get it wrong.

We ask for your patience and understanding while our large team continues to work through this difficult and complex job. [5]

The vast majority of formal identifications were completed within four weeks of the quake, and the last on 27 July 2011.

The New Zealand Police provided bereaved families with a dedicated liaison officer able to answer questions and give support. Among the many other individuals and groups who offered a range of practical and emotional help were chaplains and churches, embassy and consulate staff, the Canterbury Earthquakes Royal Commission, and the New Zealand Red Cross through its Bereaved Families Programme.

Those who lost their lives in the quake have been honoured in a number of ways. They have been remembered individually at private funerals and through floral tributes at significant sites; collectively in artworks such as Peter Majendie’s 185 Empty White Chairs; with two minutes of silence nationwide; and at public memorial and commemorative services. USAR team member Peter Seager recalls what it was like at the CTV site when the country observed two minutes’ silence exactly a week after the quake:

Lunch was timed around the planned 2 minutes silence at 12.51. We returned to Latimer Square, expecting the silence to be called within the camp itself. However, as the time approached, we were all instructed to walk down to the CTV site one block away. This included all search teams present, and support staff, including the caterers.

We walked down the road, to see the site slowly revealed. At this time, the bulk of the debris had been removed. However, the charred lift shaft remained, along with a quantity of slabs and other rubble. The site was quite shocking to those like us, who had not seen it up close before. The atmosphere was sombre and subdued. As more personnel arrived, we spread around two sides of the block.

A chaplain spoke, then the two minute silence followed, broken only by a solitary police radio. After more words, the teams were dismissed to return to Latimer Square. Already subdued by the experience, it was about to take another turn! As I walked along, I began to hear bagpipes playing Amazing Grace. As the corner of the site came closer, we could hear clapping. Where was this coming from? A group of family had been allowed in for the service and were standing on the corner applauding the rescuers as they walked by. One elderly man was holding up a photograph, possibly of his daughter. There were no words that could be exchanged and most of us carried on trying to hold in emotions until we were back at the Square! I saw one tough looking Australian fireman with tears in his eyes. There were many more.

http://www.quakestories.govt.nz/255/story/

The National Christchurch Memorial Service

A national memorial service was held in North Hagley Park on 18 March 2011. A public holiday was declared for the Canterbury region to enable as many people as possible to attend the service. Business owners trying to get back on their feet were among those who felt that it was too soon for such an event, but thousands turned out for it. Among many notable moments during the service, compelling footage of damage in the CBD was screened, the crowd spontaneously applauded the USAR teams, and Prince William conveyed words of wisdom from his grandmother, the Queen: ‘grief is the price we pay for love’.[6]

In 2016 work is under way on a Canterbury Earthquake Memorial which will be dedicated on 22 February 2017. The memorial has a dual purpose: ‘paying respect to the 185 people who lost their lives’ and acknowledging ‘the shared trauma and huge support received with the recovery operation that followed’. [7] In 2013 the government purchased the CTV and PGC sites and made a commitment to consult the bereaved families as plans for these areas were developed.

Damage

Casualties

Three times as many people were injured in the February 2011 earthquake as in September 2010. The most serious injuries were caused by falling masonry or as a result of the collapse of buildings. Limbs had to be amputated and some people suffered partial or full paralysis.

Many thousands of people suffered minor injuries similar to those sustained in the September quake. Bruises, sprains and strains were most common, followed by cuts, dislocations and broken bones. As in September, most of these people were injured during the primary earthquake, for example by tripping or falling. Others were injured during aftershocks or while cleaning up their properties.

Health workers in the city faced ‘substantial difficulties’ in caring for the injured. Most serious was the loss of electricity at the region’s only acute-care hospital, Christchurch Hospital. Other difficulties were the loss of communication systems, the scarcity of care for people before they arrived at the hospital, difficulties in the registration and tracking of patients, frightened patients, and managing the media.

Paul Gee, an emergency department doctor at Christchurch Hospital, mentions some of these issues in his account of the immediate aftermath of the earthquake:

When I arrived at the emergency department (ED), it was teeming with casualties from the central business district. The hospital disaster response plan was in full activation. A station had been set up outside the ED to deal with minor injuries. I went inside to help with the more seriously injured. There are 10 resuscitation bays and 10 monitored bays in our resuscitation area. A seriously injured patient would arrive every 5 to 10 minutes. I helped oversee and guide a number of concurrent resuscitations. All had injuries from building collapses or falling masonry.

The ED itself had been compromised by fallen ceiling tiles, and a damaged backup power supply left us in darkness for significant periods. Ongoing aftershocks also kept us on edge. We had no formal information on the extent of damage or expected casualties. Ambulance officers and patients were able to tell us snippets about collapsed buildings, fires, crushed cars and buses, etc. [8]

Despite being ‘compromised’, Christchurch Hospital was able to continue to provide care, with the support of other hospital and primary care facilities.

Psychological effects

The February earthquake and its aftershocks, like the September earthquake and aftershocks that preceded it, affected Cantabrians’ well-being in ‘complex and diverse ways’. [9] International research suggests that psychosocial recovery can take up to 10 years and with multiple events in Canterbury most residents went through the stages of recovery (described as heroic, honeymoon, disillusionment and reconstruction) more than once.

Research undertaken by the Canterbury District Health Board and the Mental Health Foundation in 2012 as part of the initiative ‘All Right?’ found that how people felt was ‘closely related to how the earthquakes impacted on their … homes, relationships, social lives, communities, identities, finances and careers’. More than 80% of those involved in the research said that their lives had changed ‘significantly’ since the earthquake, and more than two-thirds were ‘grieving for lost Christchurch’. But by this time 59% ‘strongly agreed’ that they were ‘generally happy with their life right now’ and 67% ‘strongly agreed’ that they were ‘coping well with day to day things’. Only a minority of the people who were interviewed or took part in focus groups appeared to be ‘experiencing great difficulties with their wellbeing’, including some who reported ‘symptoms of mental health problems’ such as fear, anxiety and hypervigilance. Some had increased their smoking or alcohol consumption, and fatigue was more common.

An anonymous contributor to QuakeStories describes the feelings of loss they experienced during a tour of the red-zoned CBD a few months after the quake:

The first place we came to that affected me was Victoria Square. I’d forgotten, even though I had seen pictures, that the lanterns which had been put up for the lantern festival the weekend after February 22nd were still there. The sight of them, faded, ripped and broken in some places really got to me. I had been expecting to go to that festival and to be coming to that place so many months later and having such a vivid reminder of the way life just stopped so suddenly on that day was quite startling. It set the tone for most of the way I felt on the rest of the trip – a strange sense of coming home mixed with a feeling that said, ‘what the hell is this place? Where did you put MY city?’…

Then, of course, was the cathedral. The bus stopped at three points along the way (the sites of the PGC building, the CTV building and the cathedral) but at the other two I felt like it wasn’t right to take pictures. I have several personal reasons for that, but the cathedral feels different. In a way it was really nice, in light of the news this week about the cathedral’s partial demolition, and the unexpected complicated swirl of emotions that brought up in me, to be able to get close to it and take a picture. It’s a sad sight, but it did feel good to be able to say goodbye to it before anymore of it goes and I think that’s where I’ll leave this. It was a sad day, and a challenging day but I’m glad I did it.

http://www.quakestories.govt.nz/183/story/

Property damage

The February earthquake caused widespread damage to residential and commercial properties throughout Christchurch. Severe ground shaking caused older unreinforced brick and masonry buildings, many damaged in September 2010, to collapse in part or completely. It also caused damage to more modern buildings – notably the CTV and PGC buildings, the collapse of which resulted in the deaths of 115 and 18 people respectively.

Liquefaction – ‘a liquid mush’ of soft sand and silt which had wrecked building foundations, ruptured water and sewer pipes and shattered roads, footpaths and driveways in September – struck the city again. The eastern suburbs and areas around the Avon River were again hardest hit. Whereas an estimated 31,000 tonnes of silt was cleared in Christchurch between September 2010 and February 2011, 397,025 tonnes was removed between February and June 2011. Further liquefaction followed the June and December 2011 aftershocks.

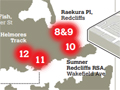

The city also faced a new problem. Dislodged boulders, collapsing cliffs, landslides and failing fill and retaining walls damaged properties and infrastructure on and below the Port Hills. Five people died when cliffs collapsed in Redcliffs, Sumner and Lyttelton.

The severe shaking, liquefaction and landslides left some 16,000 properties ‘severely damaged’, More than 90% of properties in Greater Christchurch suffered some damage in either September or February. Many of the city’s most important heritage buildings were damaged or destroyed, including the Provincial Council Chambers, Lyttelton’s Timeball Station, and both the Anglican Christchurch Cathedral and the Catholic Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament. The region also lost a number of its distinctive natural features and landmarks. Among these was Shag Rock/Rapanui (the great stern post) at the entrance to the Heathcote and Avon estuary/Te Ihutai at Sumner. This had towered 11 m above the sea but was now a small pile of rubble.

Economic damage

In 2012, the Reserve Bank concluded that Canterbury’s economy had proved ‘reasonably resilient to the impact of the earthquakes’, and that ‘the spill over to other regions’ had been limited. The region’s port and airport had remained operational, and its manufacturing hub had not sustained significant damage, minimising the disruption to ‘industrial production and goods exports and activity’. The cost of repairs and rebuilding following the February 2011 earthquake was estimated at $20 billion, compared to $5 billion following the September 2010 quake. The Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority suggested that the rebuild might cost $30 billion once improvements were included. Some sectors were hit hard, ‘notably retail, accommodation and hospitality’. The number of international guest nights had declined by just 6% after the September earthquake, but fell by a further third following the February earthquake. Language schools and other groups catering for international students were hit particularly hard, with international enrolments dropping by 57% between 2010 and 2012. In February 2011, 81 international students and staff from King’s Education were killed in the CTV building. The number of student visas for the Canterbury region dropped by 37% – around 3300 individuals – in 2011.

Individual businesses also suffered again – whether from damage to stock or buildings, the impact of damage to infrastructure such as roads and utilities, or because of a decline in the demand for their services. In Stories from Dallington (a small suburb beside the Avon River badly affected by liquefaction), Bernice Hall, the practice manager at Gayhurst Medical Centre, describes how they ‘continued to operate under very difficult conditions’ thanks to their ‘team of very dedicated doctors and staff’. Two days after the earthquake:

The building hadn’t been checked and the power was still out, so we moved a desk out to the car park, found pen, paper and the Medical Centre stamp, and the doctors were able to do prescriptions, chat to people and reassure them. They virtually had consultations in the car park. It was lucky it was fine…

Over the weekend, a neighbour very generously gave us the loan of his generator, and the building was checked by an engineer and, once the glass roof was removed from above the main door, it was given the all clear…

The first days were difficult. We were without power, water, sewerage and phones. The staff were amazing. Reception staff had to write all the patient details down as people arrived, find manual forms for things usually done electronically, and the nurses and doctors had to write notes and keep hand-written records for all procedures. By mid-morning [Monday 28th], Dr Collins had arranged for a couple of cellphones and had our Medical Centre number diverted to them. A portaloo was dropped off in the car park, and we had a delivery of bottled water. A large generator was delivered to us a week after the quake. At that stage, little did we know that it was to be with us for the next couple of months. We were also set up with a water tank, which gave us a supply inside the building, bypassing the mains supply. The portaloo was needed, along with a chemical toilet, for four long months. [10]

Footnotes

[1] Martin van Beynen (ed.), Trapped: remarkable stories of survival from the 2011 Canterbury earthquake, Penguin Books, Auckland, 2012, pp. 178–80.

[2] ‘Christchurch quake: search squads focus on rewards, not risks’, New Zealand Herald, 24 February 2011.

[3] Press, 22 February 2012, p. B11.

[4] 'Death in the classroom', Press, 10 September 2011, p. C1-5.

[5] ‘Disaster Victim Identification teams in for the long haul’, NZ Police: http://www.police.govt.nz/news/release/27378

[6] The National Christchurch Memorial Service booklet: https://gg.govt.nz/image/tid/350

[7] Christchurch Central Development Unit, 'Canterbury Earthquake Memorial': https://ccdu.govt.nz/projects-and-precincts/canterbury-earthquake-memorial

[8] Paul Gee, ‘Getting through together: an emergency physician’s perspective on the February 2011 Christchurch Earthquake', Annals of Emergency Medicine, vol. 63, no. 1, January 2014, p. 81.

[9] http://www.healthychristchurch.org.nz/media/100697/allrightresearchsummary.pdf

[10] Lois E. Daly, Stories from Dallington: a year of quakes in a Christchurch suburb, Achilles Press, Christchurch, 2010, pp. 106–8.

Further information

This article was written by Imelda Bargas and produced by the NZHistory team. It makes extensive use of contributions to QuakeStories, a website established by the Ministry for Culture and Heritage in 2011. Want to share your experience of the February earthquake? Do so here.

A feature on the post-2011 recovery of the Canterbury region will appear on NZHistory in due course.

Links

The 2010 Canterbury (Darfield) earthquake (Te Ara)

The 2011 Christchurch earthquake (Te Ara)

The shaky isles: Canterbury & other quakes (MCH)

Wellington and Christchurch's earthquake risk (Te Ara)

Canterbury Earthquakes Royal Commission. The report of the Canterbury Earthquakes Royal Commission contains biographies of those who died as a result of the earthquake in the CTV (vol. 6, pp. 5-37), PGC (vol. 2, pp. 12-18) and other buildings (vol. 4, sn 4, pp. 33-47).

Canterbury earthquakes and recovery information (Environment Canterbury)

Canterbury earthquakes (Kete Christchurch)

Canterbury earthquake for kids (Christchurch City Libraries)

Canterbury earthquake (GNS Science)

CEISMIC (University of Canterbury)

Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (CERA)

The Rebuild (Christchurch City Council)

Victims of the Quake (Press, Stuff). Obituaries of the 185 people killed in the February 2011 Christchurch earthquake

Books and articles

Martin van Beynen, Trapped: remarkable stories of survival from the 2011 Canterbury earthquake, Penguin, Auckland, 2012

G. Dellow et al., ‘Landslides caused by the 22 February 2011 Christchurch earthquake and management of landslide risk in the immediate aftermath’, Bulletin of the New Zealand Society for Earthquake Engineering, vol. 44, no. 4, December 2011

'Review of the Civil Defence Emergency Management Response to the 22 February Christchurch Earthquake', Civil Defence

David Johnston et al., ‘The 2010/2011 Canterbury Earthquakes: context and cause of injury’, Natural Hazards, January 2014

Ian McLean et al., Review of the Civil Defence Emergency Management Response to the 22 February Christchurch Earthquake, June 2012: http://www.civildefence.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/publications/Review-CDEM-Response-22-February-Christchurch-Earthquake.pdf

Miles Parker and Daan Steenkamp, ‘The economic impact of the Canterbury earthquake’, Reserve Bank of New Zealand Bulletin, vol. 75, no. 3, September 2012

Melissa Parsons, Rubble to resurrection: churches respond in the Canterbury quakes, DayStar Books, Auckland, 2014

S.H. Potter, J.S. Becker, D.M. Johnston and K.P. Rossiter, ‘An overview of the impacts of the 2010-2011 Canterbury earthquakes’, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 2015

Pete Seager and Deb Donnell, Responders: the New Zealand volunteer response teams, Christchurch earthquake deployments, Keswin Publishing, Christchurch, 2013

Janet K. Spittlehouse, Peter R. Joyce, Esther Vierck, Philip J. Schluter and John F. Pearson, ‘Ongoing adverse mental health impact of the earthquake sequence in Christchurch, New Zealand’, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 48, no. 8, 2014, pp. 756-63

Stories of resilience and innovation in schools and early childhood services: Canterbury earthquakes 2010–2012 (June 2013)*: 19/06/2013, Education Review Office, 2013

Alastair Suren, The Brigade: earthquake 2011: a tribute to the Lyttelton Volunteer Fire Brigade, Lyttelton Volunteer Fire Brigade, Lyttelton, 2012

Hugh Trengrove, ‘Operation earthquake 2011: Christchurch earthquake disaster victim identification’, The Journal of Forensic Odonto-stomatology, 12/2011, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 1–7

M. Villemure, T.M. Wilson, D. Bristow, M.Gallagher, S. Giovinazzi and C. Brown, ‘Liquefaction ejecta clean-up in Christchurch during the 2010–2011 earthquake sequence’, NZ Society for Earthquake Engineering, 2012 Conference, paper no. 131

Community contributions