Anzac Day, as we know it, began to take shape almost as soon as news reached New Zealand of the landing of soldiers on the Gallipoli Peninsula on 25 April. Within a few years core elements of the day were set and the Anzac story and sacredness of the commemoration enshrined.

1915: Gallipoli remembered

The first public recognition of the landings at Gallipoli occurred on 30 April 1915, after news of the dramatic event had reached New Zealand. A half-day holiday was declared for government offices, flags were flown, and patriotic meetings were held. People eagerly read descriptions of the landings and casualty lists – even if the latter made for grim news. Newspapers gushed about the heroism of the New Zealand soldiers.

From the outset, public perceptions of the landings evoked national pride. The eventual failure of the Gallipoli operation enhanced its sanctity for many; there may have been no military victory, but there was victory of the spirit as New Zealand soldiers showed courage in the face of adversity and sacrifice.

1916: a half-day holiday

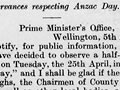

New Zealanders soon demanded some form of remembrance on the anniversary of the Gallipoli landings. This became both a means of rallying support for the war effort and a public expression of grief – for no bodies were brought home. On 5 April 1916 a half-day holiday for 25 April was gazetted, and church services and recruiting meetings were proposed.

Returned servicemen wanted something else: 'the boys don't want to be split up among twenty or thirty different churches on Anzac Day, and it is certain they don't want to go to a meeting to hear people who haven't been there [to war] spout and pass resolutions'. Instead, returned servicemen preferred a public service conducted by an army chaplain.

Returned servicemen soon claimed ownership of the day's ceremonies. These included processions of returned and serving personnel, followed by church services and public meetings at town halls. Speeches extolled national unity, imperial loyalty, remembrance of the dead and the need for young men to volunteer at a time when conscription loomed.

Large crowds attended the first commemorations in 1916. There were 2000 at the service in Rotorua, and in London, there was a procession of 2000 Australian and New Zealand troops and a service at Westminster Abbey. New Zealand soldiers in Egypt commemorated the day with a service and the playing of the last post, followed by a holiday and sports games.

Only a year after the landings some people saw potential profits from using the term Anzac to promote their products. On 31 August 1916, after lobbying by returned soldiers, the use of the word Anzac was prohibited for trade or business purposes.

Patriotism and remembrance

The New Zealand Returned Soldiers' (later Services') Association, in co-operation with local authorities, took a key role in the ceremony, organising processions of servicemen, church services and public meetings. The ceremony on 25 April was gradually standardised during and after the war.

It became more explicitly a remembrance of the war dead and less a patriotic event once the war was over. The ceremony was conducted around a bier of wreaths and a serviceman's hat, and there was a firing party of servicemen men with their heads bowed and a chaplain who read the words from the military burial service. Three volleys were fired by the guard, and the last post was played. This was followed by a prayer, a hymn and a benediction.